3.1 Geology and Geomorphology#

Parent material is a critical component of the pedogenic system and the CZ— all the other state factors of soil formation act upon the parent material to create soil, and thus the original, unweathered composition of the parent material plays a unique role in the weathered product.

The geology of a region controls the parent material available for pedogenesis. Parent material can be represented by a wide range of rock types of varying geochemical compositions, it can be lithified (hardened) or unconsolidated, and it can be relatively recent in age or billions of years old. The geologic setting of a region, past and present, also determines whether or not mountains or valleys exist, thereby exerting a first-order influence on the topographic setting in which CZ processes function and soils form. Furthermore, the geologic setting will determine whether parent material lies within an active setting, perhaps only recently exposed to pedogenic processes; or within a more stable setting in which soil formation has continued unabated for hundreds of millennia, subject only to the vagaries of climatic and biotic change.

Let’s review basic principles of geology and geomorphology.

Fundamental Geological Principles#

Geology is the scientific discipline dedicated to understanding the physical features and processes of Earth, as well as the history of the planet and its inhabitants since its origin. A basic understanding of the fundamentals of geology can enhance your appreciation of geoheritage sites and scenic vistas.

Cross-cutting Relationships#

Fig. 9 Pegmatite dikes exposed in Painted Wall cliff face. The light colored dikes are younger than the dark rock. Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, Colorado.#

James Hutton’s observations related to uniformitarianism also serve as the basis for another important geologic principle called cross-cutting relationships, which is a technique used in relative age dating. In short an intrusive rock body is younger than the rocks it intrudes. For example, Salisbury Crag, a prominent Edinburgh landmark known to Hutton, owes its relief to a thick sheet of resistant basalt. Hutton showed from the super-heated contacts below and above, and from places where the basalt actually invaded underlying and overlying beds, that the thick basalt body was not merely a flow that had formed in sequence. Rather it was intruded as hot magma into the surrounding sedimentary rocks long after they were deposited (Eicher 1976). Other similar relationships include faults being younger than the rock layers they cut and erosional surfaces being younger than the rocks they erode.

Fig. 10 Hutton’s Section on Edinburgh’s Salisbury Crags. Location: 55.9432°N 3.1672°W. Image source: Wikipedia#

Faunal Succession and Fossil Correlation#

Fig. 11 Park ranger surveys park lands for exposed fossils. Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona.#

As an engineer and surveyor, William Smith’s (1769–1839) travels acquainted him intimately with much of England’s countryside. As he investigated roads, quarries, mines, and canals, Smith recognized and traced out numerous sedimentary rock units, in which he noticed that each successive unit contained its own diagnostic assemblage of fossils. Smith’s discovery that strata may be identified by the fossils they contain became known as the law of faunal succession. Henceforth, fossils became a new tool by which geologists could distinguish rock units of different ages from one another. Faunal succession became a unifying principle by which rock units are categorized and recognized widely.

This important principle raised questions about ancient life that were not easily answered at Smith’s time, but even without answers to these questions, correlation between distant localities now became feasible. A method was established to assign a stratigraphic classification based on time relations of strata rather than on rock types, which was previously thought to indicate age. In short, this was the key discovery that stratigraphic geology needed in order to progress further (Eicher 1976).

Organic Evolution#

Fig. 12 Fossil trackway in the Coconino Sandstone (about 260 million years old) made by Chelichnus, a reptile like mammal. Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona.#

Organic evolution is the theory that more recent types of plants and animals have their origins in other pre-existing forms and that the distinguishable differences between ancestors and descendents are due to modifications in successive generations. Charles Darwin (1809–1882) did not invent the idea of organic evolution; generations preceding him entertained the notion such as the French zoologist Jean Baptist de Lamarck (1744–1829), a pioneer in invertebrate paleontology, and Erasmus Darwin (1744–1802), grandfather of Charles. Until Charles Darwin’s time, however, the idea had never had wide currency because earlier workers lacked important data and the Huttonian concept of geologic time, which are both vital for the evolutionary argument. Charles Darwin’s contribution was to propose a mechanism—natural selection—to explain how this change could occur.

Because sufficient time is required to produce changes, one of the first requirements of evolution came out of uniformitarianism. This idea provided the first link in Darwin’s chain of reasoning. The relationship between organic evolution and geologic time is that the very randomness of very small, fortuitous evolutionary variations in species, which result in noticeable changes in the physical form of an organism, requires enormous amounts of time. Building on uniformitarianism, Darwin constructed a singularly rational and convincing argument for the origin of the diverse organisms that populate the world.

Organic Extinction#

Fig. 13 Jurassic Dinosaur bones of the Morrison formation at the Quarry Exhibit Hall. Dinosaur National Monument, Utah.#

For more than 300 years, naturalists have recognized that fossils are the remains of once-living plants and animals. They postulated that formerly existing species were no longer living; that is, they had become extinct. However, the idea of extinction took a while to be proven to the satisfaction of most people. The chief reason was that the best known fossils were marine invertebrates. These are certainly as good as terrestrial organisms to demonstrate extinction, but at the beginning of the 19th century little was known of life in the oceans. Mindful of the very real limits of their knowledge, naturalists of the time hesitated to suggest that certain marine animals represented by fossils no longer existed anywhere on Earth (Eicher 1976); an organism might still be living in some deeper, unexplored part of the ocean.

Following the lead of William Smith’s work on faunal succession, George Cuvier (1769–1832), a French zoologist, worked out the stratigraphic sequences of terrestrial vertebrates and marine invertebrates in the strata of the Paris Basin. In 1812 he showed conclusively that many fossil vertebrates have no known living counterparts, and people agreed that it was highly unlikely that such big land animals would go undiscovered (Eicher 1976).

Like William Smith, Cuvier recognized distinctive fossils, but he emphasized the changes in them over time. As Cuvier carefully worked out a succession of different faunas in the strata of the Paris Basin, he noted that the younger deposits contained creatures more like those of the present day than did the older deposits (Eicher 1976). Therefore, in addition to proving the extinction of species, Cuvier demonstrated that each changing sequence of faunas represents a particular time in the geologic past.

Superposition and Original Horizontality#

Fig. 14 Cross-bedded sandstone of the Jurassic Navajo formation. Zion National Park, Utah.#

In 1669, Nicolaus Steno made the first clear statement that strata (layered rocks) show sequential changes, that is, that rocks have histories. From his work in the mountains of western Italy, Steno realized that the principle of superposition in stratified (layered) rocks was the key to linking time to rocks. In short, each layer of sedimentary rock (also called a “bed”) is older than the one above it and younger than the one below it. Steno’s seemingly simple rule of superposition has come to be the most basic principle of relative dating. Steno originally developed his reasoning from observations of sedimentary rocks, but the principle also applies to other surface-deposited materials such as lava flows and beds of ash from volcanic eruptions.

In addition, Steno realized the importance of another principle, original horizontality, namely that strata are always initially deposited in nearly horizontal positions. Thus, a rock layer that is folded or inclined at a steep angle must have been moved into that position by crustal disturbances (i.e., mountain building, faults, or plate tectonics) sometime after its deposition.

Uniformitarianism#

Uniformitarianism is a fundamental concept in geology. It asserts that the same natural laws and processes that operate today have always been at work throughout Earth’s history. In other words, the present is the key to understanding the past. Let’s delve into this principle:

Uniformitarianism suggests that Earth’s geologic processes—whether gradual or sudden—have consistently shaped the planet over time. Whether we witness an earthquake, the erosion of a river valley, or a volcano eruption, these events occur today in the same way they did in the past.

Prior to 1830, scientists adhered to the theory of catastrophism, which proposed that large, abrupt changes (or catastrophes) were responsible for shaping Earth’s features, such as mountains. However, two influential figures challenged this view:

James Hutton (1726–1797), a Scottish farmer and naturalist, observed that natural processes—like mountain-building and erosion—unfolded gradually over time. He formulated the Principle of Uniformitarianism, emphasizing the slow, continuous forces shaping Earth’s surface.

Charles Lyell (1797–1875), a Scottish geologist, further championed uniformitarianism. His book, Principles of Geology, debunked catastrophism. Lyell found evidence that sea levels had risen and fallen, volcanoes could form atop older rocks, and valleys eroded slowly due to water’s power.

The combined efforts of Hutton and Lyell laid the foundation for modern geology. Interestingly, Charles Darwin, the father of evolutionary biology, saw uniformitarianism as support for his theory of species emergence. He recognized that life’s evolution required vast spans of time, which geology confirmed.

Fig. 15 Colorado River near Nankoweap Creek. Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona.#

The Present is the Key to the Past#

Many geologists consider James Hutton to be the father of historical geology. Hutton observed such processes as wave action, erosion by running water, and sediment transport and concluded that given enough time these processes could account for the geologic features in his native Scotland. He thought that “the past history of our globe must be explained by what can be seen to be happening now.” This assumption that present-day processes have operated throughout geologic time was the basis for the principle of uniformitarianism.

Before Hutton, no one had effectively demonstrated that geologic processes occurred over long periods of time. Hutton persuasively argued that seemingly weak, slow-acting processes could, over long spans of time, produce effects that were just as great as those resulting from sudden catastrophic events. And, unlike his predecessors, Hutton cited verifiable observations to support his ideas.

Although Hutton developed a comprehensive theory of uniformitarian geology, Charles Lyell (1797–1875) became its principal advocate. Lyell was successful in interpreting and publicizing uniformitarianism for society at large. Hutton’s idea of uniformitarianism (and his cumbersome and difficult literary style) had simply failed to capture the imagination of his generation, so geologists often credit Lyell with advancing the basic principles of modern geology. Lyell’s Principles of Geology is a landmark text in the history of science and as important to modern world views as the works of Charles Darwin. In 1990 the University of Chicago Press republished his works. In the first of three volumes, Charles Lyell sets forth the uniformitarian argument: processes now visibly acting in the natural world are essentially the same as those that have acted throughout the history of the Earth, and are sufficient to account for all geologic phenomena.

Plate Tectonics#

We live on a layer of Earth known as the lithosphere which is a collection of rigid slabs that are shifting and sliding into each other. These slabs are called tectonic plates and fit together like pieces to a puzzle. The shifts and movements of these plates shape our landscape including the spectacular mountain ranges, valleys, and coastlines of our national parks. The theory of plate tectonics was revolutionary in helping us understand how these landscapes formed in the past and how they continue to change during our lifetimes.

The story of plate tectonics starts deep within the Earth. Each layer of the Earth has its own unique properties and chemical composition. The thin outer layer, the one we live on, is broken into several plates that move relative to one another. Plate boundary interactions result in earthquakes and volcanoes, and the formation of mountain ranges, continents, and ocean basins.

Fig. 16 Shaded relief map of the U.S. highlighting different tectonic settings. Superimposed in red are the more than 400 National Park System sites. Letter codes are abbreviations for parks. Image source: Plate Tectonics & Our National Parks - Geology (nps.gov)#

The dramatic topography in western US is due to its youth. Mountains and coastlines are continuously being built and deformed because they are at or near active plate boundaries. Features in the eastern US, such as the Appalachian Mountains and Atlantic Coast, formed at plate boundaries, but that was a long time ago. Now, the nearest plate boundaries are more than a thousand miles away, and the landscapes are wearing away.

Rock Cycle#

Rocks and minerals are all around us! They help us to develop new technologies and are used in our everyday lives. Our use of rocks and minerals includes as building material, cosmetics, cars, roads, and appliances. In order maintain a healthy lifestyle and strengthen the body, humans need to consume minerals daily. Rocks and minerals play a valuable role in natural systems such as providing habitat like the cliffs at Grand Canyon National Park where endangered condors nest, or provide soil nutrients in Redwood where the tallest trees in the world grow.

Rocks and minerals are important for learning about earth materials, structure, and systems. Studying these natural objects incorporates an understanding of earth science, chemistry, physics, and math. The learner can walk away with an understanding of crystal geometry, the ability to visualize 3-D objects, or knowing rates of crystallization.

Geologic Time#

In geology, we can refer to “relative time” and “absolute time” in addressing the age of geologic formations or rock units. Chronostratigraphy is the branch of geology that studies the relative time relations and ages of rock units. In chronostratigraphy, we are concerned with the age relations between rock bodies irrespective of their absolute (numerical) age. Fossils provide us with a rapid and accurate means of determining the relative age of rocks in a stratigraphic sequence. We cannot assign an absolute age to the fossils until we have a time scale. Geochronology is that branch of stratigraphy concerned with the dating and subdivision of geologic time and the establishment of time scales.

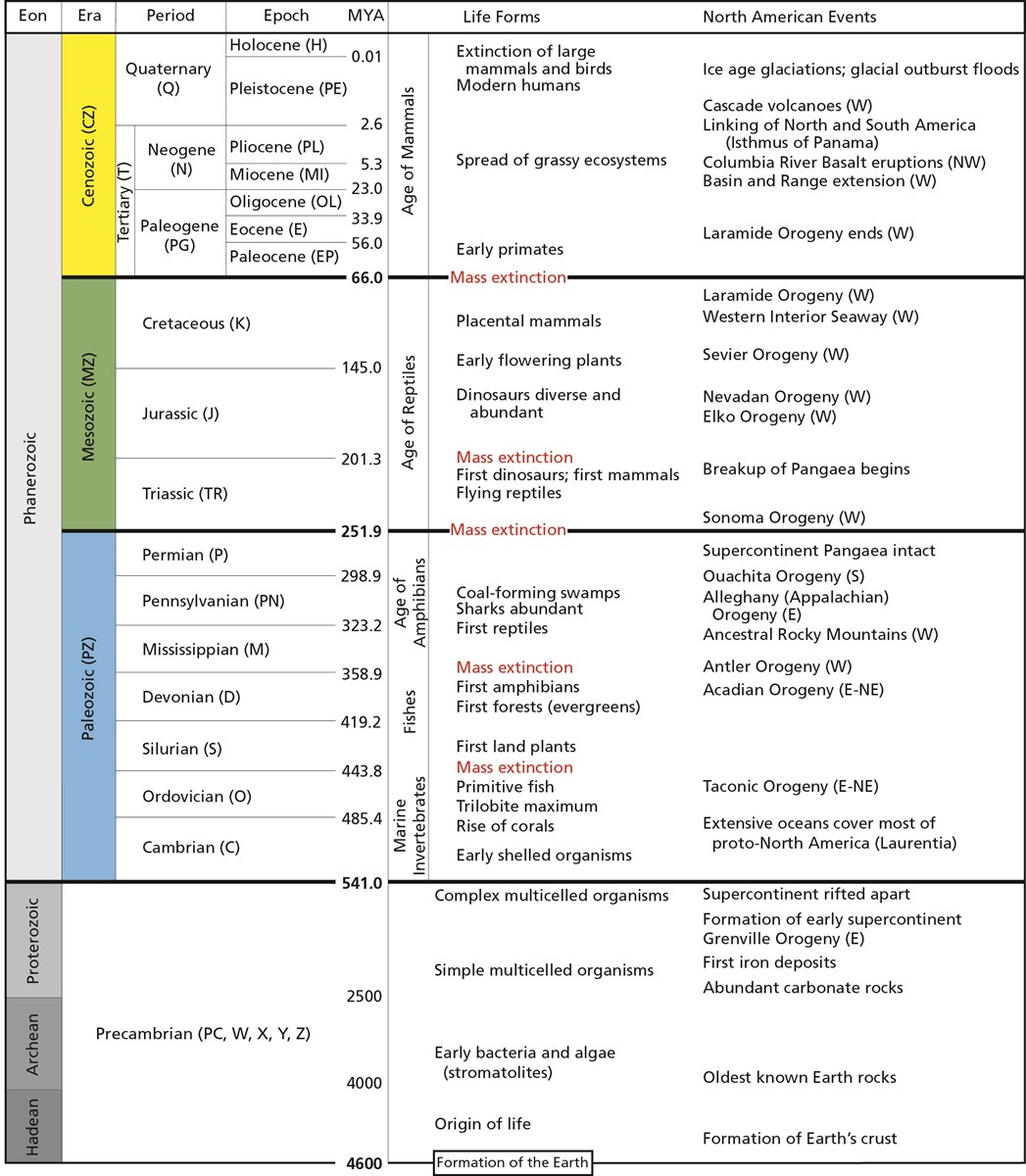

Fig. 17 Geologic time scale showing the geologic eons, eras, periods, epochs, and associated dates in millions of years ago (MYA). The time scale also shows the onset of major evolutionary and tectonic events affecting the North American continent and the Northern Cordillera (SCAK, south-central Alaska; SEAK, southeast Alaska; NAK, northern Alaska; CAK central Alaska). Image source: Geologic Time Scale - Geology (nps.gov)#

Before geologists had a means to determine the actual ages of rocks, their correlations were based on the superposition of rock strata, that is, older rocks are deposited before younger rocks. Geologic time was subdivided into a hierarchy of chronostratigraphic units of unknown duration. The application of radiometric dating techniques to determine the absolute ages of rocks resulted in the discipline of geochronology and the ability to establish geologic time scales.

There is no single location on earth that has experienced a continuous and uninterrupted accumulation of sediments or rocks that could be dated and that could yield an ideal reference time scale. A chronostratigraphic scale is not discovered; it is established by agreement among numerous geologists and is based on a composite of sections. An ideal chronostratigraphic section that would be part of a larger composite section would possess the following attributes: a sequence of points representing essentially continuous, and preferably marine, deposition; fossils that are abundant, distinctive, diverse, cosmopolitan, and well preserved, and without major paleoenvironmental changes; minerals for isotopic age determinations, and a record of geomagnetic polarity reversals. Additionally, these “type” sections would be well exposed, have reasonably permanent accessibility, and be readily correlated to other sections.

Once a chronostratigraphic scale is agreed upon, it serves as a recognized standard and generally stands unchanged until it is reevaluated and modified with even better stratigraphic sections or with improved analytical instrumentation. As a result, no chronostratigraphic scale is ever totally finalized.

A chronostratigraphic scale that is integrated with absolute ages (geochronology) is called a geologic time scale. Nearly two dozen time scales have been proposed since Arthur Holmes published his first one in 1913. Each scale incorporated the latest developments in standard stratigraphic sections, biostratigraphy, and age-dating. The latest time scale, edited in 2004 by Felix Gradstein and colleagues, incorporated high-resolution radiometric and astronomical age-dating into a comprehensive time scale for the last 3.850 billion years (the age of the earth being 4.54 billion years). No doubt the 2004 time scale will ultimately be replaced, but until then, it will serve as a reference standard to which all geologic units can be correlated and assigned an absolute age.

Geologic Time - Geology (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov)

Weathering, Erosion, and Deposition#

Fig. 18 Eroded sedimentary structures. Image source: Erosion: Water, Wind & Weather (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov)#

Jagged, fractured mountains, sloping streambanks, rugged coasts are examples of natural features that take their shape because the forces of water, wind, and weather have acted upon them over time. As the surfaces wear down, erosion moves particles away, to be deposited in other locations. Some of these features are also expressed in strata of rock formations seen in the pictures in the previous sections.

See the stream model demonstration below that shows how erosion and sediment transport modifies stream channels and geomorphology.

In-class Project

The Critical Zone can be thought of as a “feed-through reactor” in which physical denudation and erosion are closely tied to chemical weathering. Discuss the following questions based on your reading of the article: Anderson et al, 2007, Physical and chemical controls on the Critical Zone, Elements, 3(5), 315-319. Access article here.

Do you think all soil parent materials were subject to erosion and deposition?

Are some soils the result of weathering of bedrock in place, that is not subjected to erosion and deposition?

If so, how do soils developed directly from bedrock differ from soils developed on unconsolidated material, if at all?

Critical Zone (and soil) formation can be greatly affected by landscape position, particularly in actively uplifting systems. Discuss the following questions based on your reading of the article: Goodfellow et al, 2016, The chemical, mechanical, and hydrological evolution of weathering granitoid, J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf., 121, 1410-1435.

What is the progression of chemical weathering in an uplifting system?

What links exist between rock chemistry and physical properties as a function of weathering?

How do changes in rock physical properties feedback on chemical weathering?

Biota exert a fundamental role on landscape evolution and development of Critical Zone architecture. Discuss the following questions based on your reading of the article - Dietrich, W., and Perron, T., 2006, The search for a topographic signature of life, Nature, 439/26, 411-418.

How does life impact CZ architecture on long and short time scales?

What biotic mechanisms can be linked to various processes of erosion?

Do slope-dependent versus water-flow processes produce different landscapes?

Bedrock disintegration into erodable soil declines with increasing soil mantle thickness. Discuss the following questions based on your reading of the article: Heimsath, A., Dietrich, W., Nishiizumi, K., and Finkel, R., 1997, The soil production function and landscape equilibrium, Nature, 388, 358-361.

What is the relationship between soil depth and hillslope curvature?

What is a cosmogenic nuclide and how might one be used to study soil production rates?

Why might the thinnest soils and highest soil production rates be found on ridge tops?

Geomorphology#

Geomorphology is the study of Earth’s surface landforms and landform evolution. The study is both qualitative, which is the description of landforms, and quantitative, which is process-based and describes forces acting on Earth’s surface to produce landforms and landform change.

In framing how to study geomorphology, consider the three systems that intersect at and near Earth’s surface. Specifically, the geosphere, which includes the rocks comprising Earth’s crust and the global tectonic system that elevates the rocks that get sculpted into topography; the hydrosphere, which encompasses the oceans, the atmosphere, and the surface and subsurface waters that erode, transport, and deposit sediment; and the biosphere, living things that are part of ecosystems that help shape and are in turn shaped by landscape dynamics. Global patterns within and among these three basic systems set the broad regional templates within which geomorphological processes shape landforms and landscapes evolve.

The landforms and topography of a region control a variety of CZ processes. The plate tectonic setting of a region plays a first-order role in determining the topography of a site and thus in determining whether soils develop and accumulate or are subject to erosion. The overall geologic setting determines other aspects of environmental control on the CZ. Consider the following questions:

Can unique depositional environments consist of characteristic landforms? If so, what can those landforms show us about CZ processes?

Do soils developed on unique landforms or landscape positions have unique characteristics?

What is the slope and aspect of a site and how do these relate to solar heat budgets, vegetation, and CZ processes?

Mapping Bedrock and Surficial Geology#

Geologists use and create a variety of maps to display the results of our work. Among the simplest of these are maps of bedrock and surficial geology. Bedrock maps display the various rock types in a region. They are best understood if you can imagine stripping away all of the unconsolidated sediment, soil, and vegetation from the land surface down to solid rock. Bedrock maps do not indicate that XYZ rock type can be found at ABC locale; instead they show what exists in the subsurface beneath the soil and sediment and vegetation. In some places, particularly out west, rocks do exist at the surface! In that case, the bedrock map shows the rock type at the surface.

Surficial geologic maps differ from bedrock maps in that they display the sediments mantling bedrock. In some places, no sediment exists and, therefore, the surficial map may show bedrock. But in others, for example in northeastern and northwestern Pennsylvania (where multiple glaciers dumped their sediment load over the past several hundred thousand years), surficial geologic maps differentiate between the various materials moved into the region by glaciation and may even differentiate between deposits of different ice ages.

To access maps of interest see National Geologic Map Database (usgs.gov)

Mini-Project #4

Part A

Make a list of infrastructure installed at the CZO site that you are investigating. What kind of data is this infrastructure collecting? Show examples of data collected.

Part B

Go to National Geologic Map Database (usgs.gov)

Choose: “Map Catalog” from the menu bar or Choose “MapView” to explore available maps.

In “Map Catalog”, search for your study location by typing in keywords or using the map, state or county filters. If zooming in on map, click the “Use Area Shown on the Map” to set bounding coordinates for the search. Click “Search” at the bottom of the page once filters are set. In “Map View”, perform a “Go to Location,” by clicking on the crosshair symbol in the far right tool bar to zoom to your study site as the location.

In “Map Catalog”, use the “Themes” section to select bedrock and surficial from the “Geology” drop-down menu, then click Search. Conduct similar searches using the “Resources” and “Hazards” drop-down menus.

Click on the most relevant maps from the search results to assess the available mapping resources for your study site.

(1) Find and download the following four maps from your study site. For each map, provide a short description of where the map is from, the scale, and what it shows about the geology of the area.

Bedrock geology map

Surficial geology map

Resource map

Hazards map

(2) Is your study site area well covered by geologic maps or are there gaps in coverage?

(3) What do the maps you found tell you about CZ architecture at your site? How would the geology at your site influence soil formation rates?